Authored by Joshua Stylman via substack,

The Corporate Veil – America’s Hidden Transformation

Executive Summary:

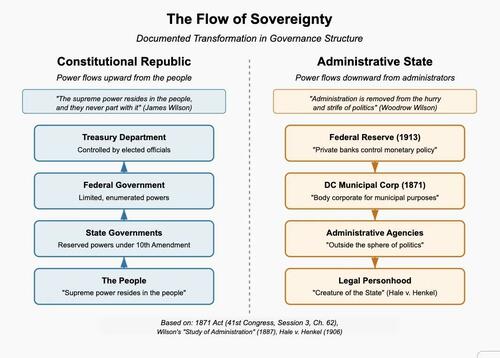

What if the America you pledge allegiance to isn’t the one running the show? This investigation examines how America’s governance system fundamentally transformed since 1871 through a documented pattern of legal, financial, and administrative changes. The evidence reveals a gradual shift from constitutional principles toward corporate-style management structures – not through a single event, but through an accumulation of incremental changes spanning generations that have quietly restructured the relationship between citizens and government.

This analysis prioritizes primary sources, identifies patterns across multiple domains rather than isolated events, and examines timeline correlations – particularly noting how crises often preceded centralization initiatives. By examining primary sources including Congressional records, Treasury documents, Supreme Court decisions, and international agreements, we identify how:

-

Legal language and frameworks evolved from natural rights toward commercial principles

-

Financial sovereignty transferred incrementally from elected representatives to banking interests

-

Administrative systems increasingly mediated the relationship between citizens and government

This evidence prompts a fundamental reexamination of modern sovereignty, citizenship, and consent in ways that transcend traditional political divisions. For the average American, these historical transformations have concrete implications. The administrative systems created between 1871-1933 structure daily life through financial obligations, identification requirements, and regulatory compliance that operate largely independent of electoral changes. Understanding this history illuminates why citizens often feel disconnected from governance despite formal democratic processes – the systems managing key aspects of modern life (monetary policy, administrative regulation, citizen identification) were designed to operate with substantial independence from direct citizen control.

While mainstream interpretations of these developments emphasize practical governance needs and economic stability, the documented patterns suggest the possibility of more fundamental changes in America’s constitutional structure deserving closer scrutiny.

I stumbled across a peculiar reference to the 1871 Act while browsing on Twitter. The post suggested that the United States had undergone a secret legal transformation in 1871, converting it from a constitutional republic into a corporate entity where citizens were treated more like assets than sovereigns. What caught my attention wasn’t the claim itself, but how confidently it was stated – as if this fundamental transformation of America was common knowledge.

My first instinct was to dismiss it as yet another internet conspiracy theory. A quick Google search led to a PolitiFact ‘fact-check’ dismissing the entire concept as ‘Pants on Fire’ false. What’s striking isn’t just the brevity with which they dismiss a complex historical question, but their methodology. They interviewed exactly one legal expert, cited no primary documents from the Congressional Record, examined none of the subsequent Supreme Court cases that reference federal corporate capacity, and ignored the documented financial transformation that followed. I’ve noticed that when establishment fact-checkers reject claims with such dismissive certainty while conducting minimal investigation, it often signals something worth examining more carefully. This pattern prompted me to check the actual Congressional Record myself. That first document pulled a thread that unraveled into this investigation. Like finding an unexpected door in a familiar house, I couldn’t help but wonder what else I’d been walking past without noticing.

This analysis unfolds through several interconnected sections: First, we’ll examine the historical context of the 1871 Act that reorganized Washington DC using corporate terminology, and explore the emergence of three influential power centers (London, Vatican City, and Washington DC) with documented financial and diplomatic connections. Next, we’ll trace the transformation of governance structures between 1913-1933, focusing on Wilson’s administrative state and the Federal Reserve’s establishment. We’ll then analyze the evolution of legal frameworks that redefined citizenship and the monetary system, particularly the dual identity concept distinguishing natural persons from legal entities. Finally, we’ll examine modern sovereignty through the Ukraine case study, before offering reflections on reclaiming authentic governance. Throughout, we’ll prioritize primary sources and pattern recognition over isolated coincidences, inviting readers to examine the evidence and draw their own conclusions.

Behind the National Illusion

When I investigated further, I discovered that in 1871, an event did indeed occur in Washington DC that deserves closer examination. The “Act to Provide a Government for the District of Columbia” was passed in the aftermath of the Civil War, at a time when the United States was deeply in debt to international banking interests. While conventionally understood as a simple municipal reorganization, this legislation contains peculiar language and structures that raise profound questions about its broader implications.

The Act established a “municipal corporation” for DC with specific language that differs markedly from previous founding documents at a time of significant changes in international finance.

E.C. Knuth’s meticulously researched work The Empire of The City documents how the passage of this Act occurred during a period when the international financial powers centered in the City of London were actively restructuring their relationships with nation-states. Knuth presents compelling evidence about the changing nature of sovereignty during this period, backed by extensive documentation from the Congressional Record and other primary sources.

Our understanding of institutions is often shaped by unseen influences. As Edward Bernays observed, “We are governed, our minds are molded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of.” This compels us to wonder: Might our fundamental understanding of national structure itself be yet another manufactured reality designed for public consumption?

When we examine how various aspects of our reality operate by decree rather than by natural law or genuine consent, we might ask whether our conception of national sovereignty itself might be another form of fiat reality.

The patterns of governance transformation identified above did not emerge in isolation. This systematic transformation follows what historian Anthony Sutton documented as a pattern of financial-political collusion transcending apparent ideological divisions. In his work Wall Street and the Rise of Hitler, Sutton revealed that Chase Bank, controlled by the Rockefellers, continued to collaborate with Nazi Germany even after Pearl Harbor, handling Nazi accounts through their Paris branch until 1942. This demonstrates how financial power operates independently of national policy or supposed wartime loyalties.

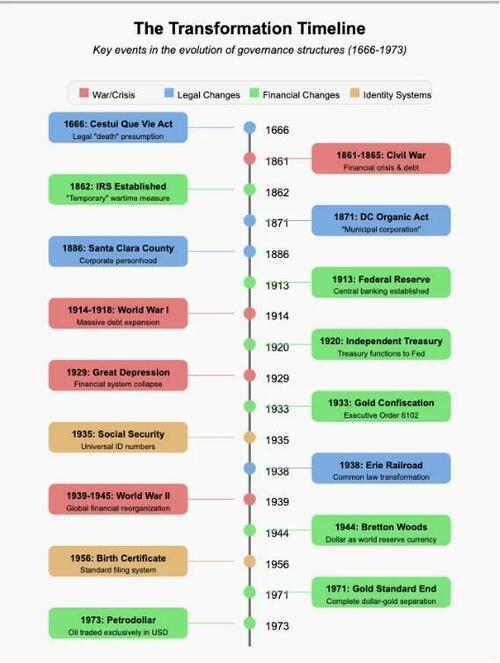

This evolutionary process follows a historical trajectory that began centuries earlier but accelerated significantly after 1871. Understanding this timeline reveals how governance structures evolved incrementally through a series of seemingly unrelated developments that, viewed collectively, suggest a coordinated pattern.

Three Centers of Power: A Documented Pattern

Knuth’s research identifies three centers that appear to function with unusual sovereignty and influence. Each merits more rigorous analysis:

The City of London – Not to be confused with London proper, ‘The City’ is a 677-acre zone with its own governance structure, police force, and legal status. Parliamentary records confirm that it operates under special legal exemptions. Financial records indicate it handles approximately 6 trillion dollars in daily transactions. Despite this enormous financial power, how many educational institutions teach about its unique status? The Corporation maintains unique historical privileges including its own police force and electoral system where voting rights are granted primarily to businesses rather than residents – an unusual arrangement that prioritizes financial interests over traditional democratic representation. While it enjoys significant independence in its internal affairs and financial operations, it ultimately remains subject to UK parliamentary sovereignty.

Vatican City – Officially recognized as the world’s smallest sovereign state, it maintains diplomatic relations with 183 countries and operates under its own legal system. Its historical influence on global affairs is extensively documented through primary sources.

Washington, DC – Created explicitly as a district outside the jurisdiction of any state, DC’s governance structure was fundamentally altered by the 1871 Act. The Congressional Record contains the full text of this reorganization, which uses language consistent with corporate formation rather than constitutional governance.

What’s particularly intriguing about these three centers is their documented interrelationships. Financial records reveal significant transactions between banking interests in all three, such as the 1832 Rothschild family loan of £400,000 to the Holy See and the 1875 purchase of Suez Canal shares by the British government with Rothschild backing. Diplomatic archives demonstrate coordinated policy positions that preceded public announcements, exemplified by President Roosevelt’s 1939 appointment of Myron C. Taylor as the U.S. representative to the Vatican to align policies during the tumultuous pre-war period. Recently uncovered Vatican documents reveal another dimension of these diplomatic channels: secret communications between Pope Pius XII and Adolf Hitler in 1939, facilitated by Prince Philipp von Hessen as a liaison. These back-channel negotiations occurred even as the United States and Britain were developing their own official positions toward Nazi Germany. Historical records further show how these centers acted in concert during major global transformations, including the coordinated approach to post-World War II reconstruction efforts where Vatican support aligned with Washington’s strategic initiatives. These documented connections suggest patterns of collaboration that transcend mere coincidence.

The visual symbolism of these power centers is equally revealing. Each maintains its own flag representing autonomous authority: the City of London with its crimson sword and dragon shield bearing the motto “Domine Dirige Nos” (Lord, direct us); Vatican City with its gold and silver keys beneath the papal tiara; and Washington DC with its three red stars on horizontal bars. While their appearances differ, each employs emblems of specific forms of authority – financial, military, and spiritual – creating a visual language of power that reinforces their special status.

The documented relationships between these three centers represent nodes in a broader network of financial power that transcends national boundaries and stated policies. The coordination within this network is evidenced by Anthony Sutton’s research in Wall Street and the Bolshevik Revolution, which documented that William Boyce Thompson, director of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, personally donated $1 million to the Bolsheviks in 1917 and arranged American Red Cross Mission support – this while the United States officially opposed the communist revolution. Such contradictions illustrate how financial interests operate above national policy, with the three centers serving as primary hubs in a global system where banking power routinely supersedes governmental authority.

The City of London maintains unique historical privileges and administrative autonomy while remaining ultimately subject to UK sovereignty. Vatican City functions as a recognized sovereign state with diplomatic relations, while Washington DC operates under federal jurisdiction but with governance structures distinct from U.S. states. Each has specialized in a different domain of power – financial, ideological, and military respectively.

Even their physical features share curious similarities. As noted in historical architecture studies, each prominently displays an ancient Egyptian obelisk. While mainstream historians attribute this to neoclassical fashion, we might reasonably ask whether these identical symbols in three centers of power might carry deeper significance, especially given the documented connections between these entities in financial and diplomatic archives. As architectural historians like James Stevens Curl have documented in works such as The Egyptian Revival, Egyptian motifs including obelisks became prominent features in Western civic and financial architecture during the 18th and 19th centuries, coinciding with the expansion of banking institutions and centralized governance. It’s worth noting that despite their prominence in these centers of power, most educational curricula rarely mention these architectural connections or their potential significance – raising questions about what other important historical patterns remain outside standard educational frameworks.

These three power centers did not emerge independently. Their development follows a historical pattern of legal and financial changes beginning with the 1871 Act’s corporate restructuring of Washington D.C.. The City of London had already established its unique financial autonomy centuries earlier, while Vatican City would formalize its sovereignty in the 1929 Lateran Treaty. Their evolution accelerated through the early 20th century as banking models and governance structures increasingly aligned, particularly during key financial reforms of the 1913-1944 period documented by financial historians. Understanding this timeline reveals how governance structures transformed incrementally through seemingly unrelated developments that, viewed collectively, point to a coherence rarely acknowledged in mainstream accounts.

Historical Context (1871-1913)

The 1871 Act and DC Reorganization

The Act established a “municipal corporation” for DC with specific language that differs markedly from previous founding documents. What’s particularly intriguing is the timing – coming after a devastating civil war that had left the country financially vulnerable, and coinciding with significant changes in international finance.

The text of the Act, preserved in the Library of Congress (41st Congress, Session 3, Chapter 62), specifically states in Section 2 that it “created a body corporate for municipal purposes” with the power to “contract and be contracted with, sue and be sued, plead and be impleaded, have a seal, and exercise all other powers of a municipal corporation.” This corporate designation, while ostensibly for administrative efficiency, uses language typically reserved for commercial entities rather than sovereigns – a fact noted in subsequent Supreme Court cases including Metropolitan Railroad Co. v. District of Columbia (1889), which affirmed DC’s status as “a municipal corporation, having a right to sue and be sued.”

Modern legal scholars remain divided on the broader implications of this Act. Conventional interpretations, such as those expressed by constitutional scholar Akhil Reed Amar, view it as a pragmatic municipal reorganization with limited scope beyond the District itself. However, the timing and language of the Act, coinciding with significant shifts in international finance during a period of national rebuilding, invites deeper examination. Rather than arguing, as some have done, that this Act definitively transformed the entire nation into a corporation, we might more accurately observe that it represented a significant step in a broader pattern of governance changes that accelerated in the decades that followed – particularly in how the relationship between citizens, government, and financial institutions evolved.

The distinction between Washington DC as a governmental entity and corporate structures bearing similar names deserves careful examination. In 1925, a corporation called the ‘United States Corporation Company’ was indeed chartered in Florida (see Articles of Incorporation filed July 15, 1925). However, rather than being the federal government itself, this entity appears to have been a corporate services provider whose stated purpose included acting as ‘fiscal or transfer agent’ and helping form other corporations. Its authorized capital was a modest $500 with only 100 shares and three initial directors from New York. The company’s connection to government remains debated – some researchers note its offices at 65 Cedar Street in New York City coincided with addresses used by Federal Reserve operations, while mainstream historians regard it as simply one of many corporate service providers established during that period of American business expansion.

It’s important to distinguish between adopting corporate-style management principles and actual corporate conversion. What the evidence suggests is not that the United States literally became a corporation, but rather that governance increasingly adopted corporate-style features: centralized management, administrative hierarchies separated from stakeholders (citizens), and operation through legal frameworks more aligned with commercial than constitutional principles. This distinction matters because it acknowledges the nuance in this historical development.

The Congressional debate surrounding the 1871 Act focused primarily on administrative efficiency rather than constitutional transformation. Representative Halbert E. Paine, who reported the bill, described it as addressing ‘the inconvenient and cumbersome organization’ of the District’s government, with discussions centered on practical governance challenges rather than fundamental sovereignty questions.

International Banking Developments

Building on Knuth’s documentation of the City of London’s influence mentioned earlier, additional sources provide further context about international financial developments during this period.

The Prussia Gate series by Will Zoll provides extensive documentation on how central banking systems evolved across multiple countries, often using nearly identical legislation despite different cultural and economic contexts. Treasury archives confirm that banking families like the Rothschilds maintained correspondence specifically discussing central banking structures with government officials across national boundaries during this period, suggesting coordination that transcended national interests.

Zoll’s research presents compelling evidence that the City of London Corporation operated with remarkable independence from British law, functioning almost as a sovereign entity within Britain. Financial records confirm its status as a “free-trade zone” since the 11th century, creating a unique structure that attracted banking operations from throughout Europe.

The historical evidence suggests patterns worth investigating: economic crises, followed by coordinated media messaging, followed by legislation that centralized financial power. This sequence appears repeatedly in Treasury records and Congressional debates preceding the Federal Reserve Act of 1913.

Transformation of Governance (1913-1933)

Mechanisms of Control: Historical Context

The document shared from Michael A. Aquino’s work MindWar introduces concepts about psychological influence that provide an illuminating framework for examining historical events. Aquino, notably a former military intelligence officer who founded the Temple of Set after leaving the Church of Satan, identified specific patterns in how public opinion is systematically shaped. His analytical concepts include ‘false-flag operations’ (events staged to appear as if conducted by others) and ‘drum-beating’ (the repetition of claims until they’re accepted as truth regardless of evidence). Aquino’s frameworks raise compelling questions about how public perception has been influenced throughout history, despite their controversial origins.

Historical records show coordinated messaging across multiple publications and political speeches in the periods preceding major financial reforms. For example, the banking panics of 1893 and 1907 were followed by remarkably similar narratives in major newspapers about the need for centralized banking – despite the fact that these same publications had previously opposed such measures.

The pattern recognition approach helps us identify when seemingly independent institutions are acting in coordination. When we examine major policy shifts like those during Wilson’s administration, following the money often reveals motivations that official histories omit.

Wilson’s Administrative State: The Paradigm Shift

Edward Mandell House, commonly known as Colonel House (though he never served in the military, the title being honorary in Texas), was President Wilson’s most trusted advisor and confidant from 1912 to 1919. Born to English immigrant parents with banking connections, House was a wealthy Texan with deep ties to international financial elites. Before advising Wilson, he orchestrated the election of several Texas governors and cultivated relationships with banking and industrial power players in both America and Europe. House was instrumental in the creation of the Federal Reserve, aligning U.S. monetary policy with global banking interests. He was also a founding member of the Council on Foreign Relations, a key architect of the Treaty of Versailles, and a driving force behind the League of Nations, which laid the groundwork for modern supranational governance. His 1912 political novel, Philip Dru: Administrator, eerily foreshadowed Wilson-era policies, describing an idealized dictator who implements sweeping progressive reforms through executive authority rather than democratic means. Despite holding no official government position, House wielded influence over Wilson’s administration in a way that modern observers might compare to the role of unelected power brokers in contemporary politics.

The mysterious nature of House’s influence was captured by House himself when he wrote in his diary: ‘The President is not a strong character… but is by no means as weak as he appears. He has an analytical mind, but not much executive ability, and has a single-track mind.’

In his 1887 essay “The Study of Administration,” Wilson explicitly advocated for a government run by ‘experts’ insulated from public opinion: ‘The field of administration is a field of business. It is removed from the hurry and strife of politics… Administrative questions are not political questions.’ He argued directly that ‘The many have no business with the selection of technical administrators any more than they have with the selection of scientists.’ These writings reveal Wilson’s profound belief in governance by unelected technical experts rather than democratic processes—a vision that laid the groundwork for the modern administrative state.

This philosophy of governance – creating a permanent administrative class operating independently of elected officials – marks a profound departure from the constitutional system established by the Founders. James Madison’s writings in the Federalist Papers explicitly warned against exactly this type of arrangement, where unelected officials would hold unchecked power over citizens. The relationship between Colonel House and Wilson point toward questions about the intentionality behind administrative systems developed during this period. As we’ll see later, this vision would eventually extend beyond domestic agencies to reshape global governance itself.

What can be verified in the historical record is that during Wilson’s administration, several mechanisms were indeed established that fundamentally altered the relationship between citizens and government – including the Federal Reserve System, income taxation, and later the Social Security system with its universal numerical identification. These systems, while presented as public benefits, effectively created trackable financial identities that constitutional scholars like Edwin Vieira Jr. have analyzed as potential instruments of financial monitoring and control. As Vieira argues, these mechanisms transformed the citizen-state relationship into one increasingly mediated through financial institutions rather than direct constitutional protections.

Wilson’s vision was deeply intertwined with both class and racial prejudices. Historical records document his belief that only people of a certain education, social class, and background possessed the capacity for wise governance of everyone else. In the name of democracy, he effectively advocated for a class oligarchy as the ruling paradigm.

As Jeffrey Tucker has noted in his analysis of Wilson’s ideology, “We find the roots of the ideology of the administrative state in the works of Woodrow Wilson, and it takes only a few minutes of reading his deluded fantasies of how science and compulsion would forge a better world to see that it was only a matter of time before the whole experiment was in tatters.” This dream – a government of administrative agencies informed by captured science – has increasingly lost credibility, particularly after the governmental failures witnessed during the Covid era. This administrative state laid the essential groundwork for today’s technocratic governance – the fusion of unelected bureaucracy with digital technologies that creates unprecedented capabilities for population management through automated systems and algorithmic decision-making.

The corporate implications of the 1871 reorganization were further reinforced in subsequent court decisions. In Hooven & Allison Co. v. Evatt (324 U.S. 652, 1945), the Supreme Court distinguished between different meanings of “United States,” including “the United States as a sovereign entity” versus “a federal corporation.” More recently, in Clearfield Trust Co. v. United States (318 U.S. 363, 1943), the Court held that “the United States does business on business terms” when it issues commercial paper – a ruling that confirmed the federal government’s capacity to function as a commercial entity rather than solely as a sovereign power. What’s particularly striking about Wilson’s administrative vision is how perfectly it aligns with the potential corporate transformation represented by the 1871 Act. Both replace government by consent with management by expertise. Both create structures that insulate decision-makers from public accountability. Both shift power from elected representatives to unelected administrators.

The evidence suggests we should ask whether Wilson’s administrative state was simply the visible manifestation of a deeper transformation that had already occurred decades earlier – the conversion of a constitutional republic into a managed corporate entity.

This administrative governance model has expanded far beyond domestic agencies to encompass international institutions that exercise significant authority with minimal democratic oversight. Organizations such as the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, World Health Organization, and Bank for International Settlements operate through similar expert-driven, technocratic frameworks. These institutions make policy decisions affecting billions of people worldwide while remaining largely insulated from democratic processes – the precise governance model Wilson advocated. This represents a shift from governance based on the consent of the governed to governance by technical expertise and financial influence that transcends national boundaries, suggesting Wilson’s vision has reached its fullest expression not in domestic bureaucracies but in the global governance architecture that emerged in the decades following his presidency.

Anyone who lived through the COVID-19 pandemic witnessed this model in full operation, as public health technocrats issued mandates affecting every aspect of daily life with minimal legislative oversight or democratic input.

This technocratic governance model, where technical experts rather than elected representatives make consequential decisions, has expanded dramatically in recent decades. As detailed in “The Technocratic Blueprint,” technological capabilities have enabled unprecedented implementation of Wilson’s vision – creating systems where algorithms and unelected specialists increasingly determine human outcomes while maintaining the appearance of democratic processes.

The Federal Reserve and National Debt Structure

The Creation of a New Financial Architecture

The Federal Reserve Act of 1913 established a central banking authority for the United States, ostensibly to provide “a safer, more flexible, and stable monetary and financial system” according to official histories. Since the abandonment of the gold standard (1931 in the UK and 1971 in the US), most nations use fiat currency with no intrinsic value beyond government decree and public confidence. Financial commentator Martin Wolf of the Financial Times has observed that only about 3% of money exists in physical form, with the remaining 97% being electronic entries created by banks. This fundamental transformation of money from a physical store of value to largely digital entries represents one of the most significant yet least understood changes in modern economic life.

However, primary documents from the Congressional Record reveal serious concerns raised during its formation.

The timing of this legislation is particularly significant. Treasury records confirm that America was experiencing financial difficulties during this period, making the country vulnerable to external financial interests. The Federal Reserve Act in 1913 established a system in which private banking interests rather than elected representatives would now be able to increasingly dictate monetary policy. While no single document explicitly confirms a private acquisition of U.S. financial sovereignty, the establishment of the Fed can arguably be seen as just that.

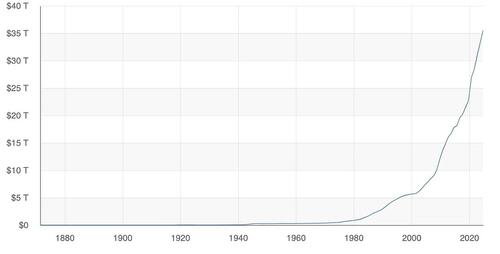

As well documented by economist Murray Rothbard in The Case Against the Fed, the Federal Reserve System created a mechanism through which private banks gained unprecedented control over national monetary policy while maintaining the appearance of government oversight. Notably, the national debt expanded dramatically following the Federal Reserve’s establishment.

The Jekyll Island Meeting: Documented Secrecy

As financial historian G. Edward Griffin documents in The Creature from Jekyll Island, the Federal Reserve meetings were conducted in extreme secrecy. The Jekyll Island meeting occurred November 22-30, 1910, with specific participants including Senator Nelson Aldrich (Rockefeller’s son-in-law), Henry P. Davison (J.P. Morgan’s senior partner), Paul Warburg (representing the Rothschilds and Kuhn, Loeb & Co.), Frank Vanderlip (President of National City Bank, representing William Rockefeller), Charles D. Norton (President of First National Bank of New York), and A. Piatt Andrew (Assistant Secretary of the Treasury).

Sutton’s analysis in The Federal Reserve Conspiracy calculated that the Jekyll Island meeting participants represented banking interests estimated by Sutton to represent approximately one-fourth of the total wealth of the world at that time. This concentration of financial power in a clandestine meeting designing what would become America’s central banking system reveals the magnitude of this transformation of monetary sovereignty.

This gathering of government officials and private bankers collaborating to design the nation’s monetary system was later confirmed by participant Frank Vanderlip himself, who admitted in the February 9, 1935 Saturday Evening Post: “I was as secretive, indeed as furtive, as any conspirator… I do not feel it is any exaggeration to speak of our secret expedition to Jekyll Island as the occasion of the actual conception of what eventually became the Federal Reserve System.” This secrecy extended to the bill’s passage—rushed through Congress on December 23, 1913, just before Christmas when many representatives had already left Washington, ensuring minimal debate. Let that sink in for a moment: the architects of our monetary system explicitly compared themselves to conspirators, working in secret to reshape a nation’s financial foundation. When I first read Vanderlip’s admission, I had to check multiple sources to believe it wasn’t fabricated.

While conventional financial historians acknowledge these meetings took place, they typically frame them as necessary collaboration between public and private sectors to create a more stable banking system following the Panic of 1907. The Federal Reserve’s official history emphasizes its creation as a response to repeated financial crises rather than as a transfer of sovereignty. However, the documented secrecy of these proceedings and the subsequent exponential growth of national debt warrant deeper examination of whose interests were ultimately served.

Congressional Warnings and Debt Expansion

Congressman Charles Lindbergh Sr. warned on the House floor: “This Act establishes the most gigantic trust on earth… When the President signs this bill, the invisible government by the Monetary Power will be legalized.” These concerns weren’t merely speculative – Treasury Department records confirm that national debt grew exponentially in the decades following the Federal Reserve’s establishment, thus making our nation beholden to supranational banking entities.

Question of Legitimate Debt

Such historical developments prompt important questions about the legitimacy of national debt, connecting to what jurisprudence experts would later term ‘odious debt.’

A doctrine, formally developed by Alexander Sack in Les Effets des Transformations des États sur leurs Dettes Publiques et Autres Obligations Financières, establishes that debts incurred by a regime for purposes that do not serve the interests of the nation do not obligate its people. Income tax in the UK began in 1799 as a temporary measure to fund the Napoleonic Wars. It was withdrawn in 1816 but reintroduced in 1842, and has remained ever since, despite its origins as a wartime emergency measure. The perpetuation of supposedly ‘temporary’ financial measures is a pattern worth examining in the evolution of state financial structures. As noted by historian Martin Daunton in Trusting Leviathan: The Politics of Taxation in Britain, 1799-1914, many of our modern financial institutions began as emergency wartime measures that were later normalized.

While Sack’s doctrine of ‘odious debt’ was traditionally applied only to authoritarian regimes, law professor Odette Lienau at Cornell Law School has expanded this analysis in ‘’Rethinking Sovereign Debt.’ Lienau questions whether even democratic nations truly maintain meaningful public consent for certain financial obligations, particularly those imposed through structural adjustment programs. This broadened framework raises intriguing questions about American national debt. Treasury documents show that U.S. national debt is uniquely structured in ways that suggest similar principles of questionable consent might apply to our own financial obligations. The mechanisms by which this debt is collateralized remain largely unexplored in mainstream economic discussions.

These documented transformations in banking authority collectively represent a profound shift in where monetary power resided. While 19th century Americans understood money creation as a function of elected representatives, these sequential legislative changes gradually relocated this power to institutions operating at arm’s length from electoral accountability. This transition in financial sovereignty laid the groundwork for even more consequential changes in monetary standards that would soon follow.

The Gold Standard Transition

The transfer of financial authority from elected officials to banking interests accelerated significantly with the Independent Treasury Act of 1920. This legislation (found in United States Statutes at Large, Volume 41, page 654, now codified at 31 U.S.C. § 9303) explicitly abolished the offices of Assistant Treasurers of the United States and authorized ‘the Secretary of the Treasury… to utilize any of the Federal reserve banks acting as depositaries or fiscal agents of the United States, for the purpose of performing any or all of such duties and functions.’ This represented a profound shift, as the Act states the Secretary could transfer these functions ‘notwithstanding the limitations of section 15 of the Federal Reserve Act,’ which had originally restricted Federal Reserve banks to only specific fiscal agent functions and maintained certain Treasury independence. The language of the Act demonstrates how banking functions once performed directly by Treasury officials were legally transferred to the Federal Reserve system less than seven years after its creation.

House Joint Resolution 192 (1933), which suspended the gold standard during the Great Depression as a supposedly temporary emergency measure, contains language that some legal analysts interpret as fundamentally altering the relationship between citizens and government debt. By removing gold backing from currency and prohibiting ‘payment in gold,’ this resolution created a system where, as some monetary historians argue, debt instruments became the only available medium of exchange.

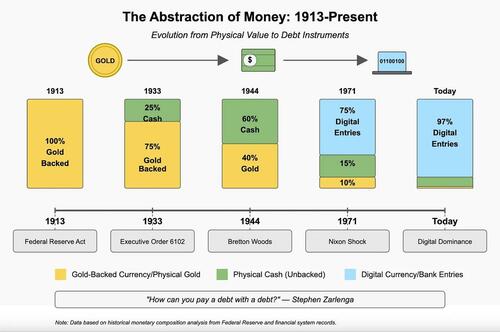

The evolution from commodity-backed currency to pure fiat money followed a clear timeline of increasing abstraction and coordination between financial centers:

-

1913-1933: The Federal Reserve Act created a central banking system modeled after the Bank of England, with founders like Paul Warburg maintaining direct ties to European banking interests. While currency remained officially gold-backed, the governance structures of Washington and London’s financial systems became increasingly aligned.

-

1933-1934: Executive Order 6102 and the Gold Reserve Act ended domestic gold convertibility, requiring citizens to exchange gold for Federal Reserve notes. This period saw increased financial coordination between the Vatican Bank (founded 1942) and Western banking interests as gold flows centralized among these institutions.

-

1944: The Bretton Woods Agreement established the dollar as the global reserve currency, with formal mechanisms for coordination between these financial centers. The IMF and World Bank were created with governance structures that ensured London maintained significant influence while the Vatican secured privileged financial relationships.

-

August 15, 1971: President Nixon unilaterally terminated dollar convertibility to gold, completing the transition to fiat currency. This final step cemented a global financial architecture in which the three power centers operated through interlocking directorates and financial relationships independent of gold’s constraints.

While the chart shows increasing digitization, the fundamental issue isn’t the digital format itself. The concept behind technologies like Bitcoin – creating digital assets with properties that could potentially resist centralization – illustrates that digitization alone isn’t the problem. The core concern is money becoming mere accounting entries in a centralized ledger that can be adjusted without the constraints that physical gold once imposed.

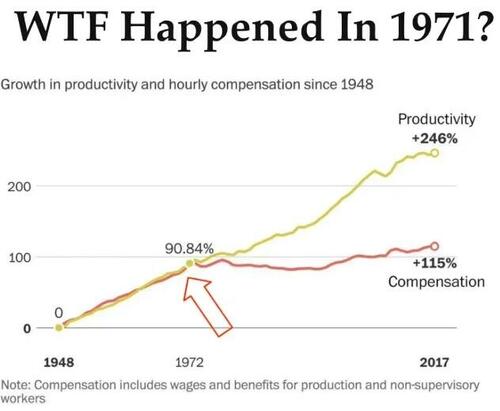

Perhaps no chart better illustrates the tangible impact of this monetary transformation than the divergence between productivity and worker compensation that began precisely when the United States abandoned the gold standard completely in 1971.

When Federal Reserve notes replaced gold-backed currency, it created a system in which, as monetary historian Stephen Zarlenga notes, we are “being asked to pay debts but all we are given from the system is debt notes, aka fiat money, to pay back those debts.” This monetary paradox presents a fundamental contradiction: ‘How can you pay a debt with a debt?’

Legal Framework Transformation

Shifts in Legal Philosophy

The documentary discrepancies when comparing the Constitution to subsequent legal frameworks, particularly the Uniform Commercial Code that now governs most commercial transactions, reveal significant shifts in legal philosophy. Legal historians have documented how common law principles were gradually replaced by admiralty and commercial law concepts.

Erie Railroad Co. v. Tompkins (1938) fundamentally altered the application of law in federal courts by ruling that federal courts must apply state common law rather than federal general law in diversity cases. Scholars have noted this represented a significant shift away from common law principles toward commercial and statutory frameworks. Within this evolving legal landscape, Title 28 U.S.C. § 3002(15)(A) provides a particularly interesting definition, stating that ‘United States’ means ‘a Federal corporation.’ While conventional legal interpretation views this as simply defining the United States’ ability to function as a legal entity for practical purposes, some researchers suggest it may have deeper implications for sovereignty.

The distinction between ‘legal’ and ‘lawful’ reflects a philosophical tension between natural law concepts and statutory frameworks that dates back centuries in Anglo-American jurisprudence. As legal historian Albert Venn Dicey noted in his seminal work ‘Introduction to the Study of the Law of the Constitution‘ (1885), ‘lawful’ acts align with common law traditions and inherent natural rights, while ‘legal’ acts derive their validity purely from statutory law created by the state.

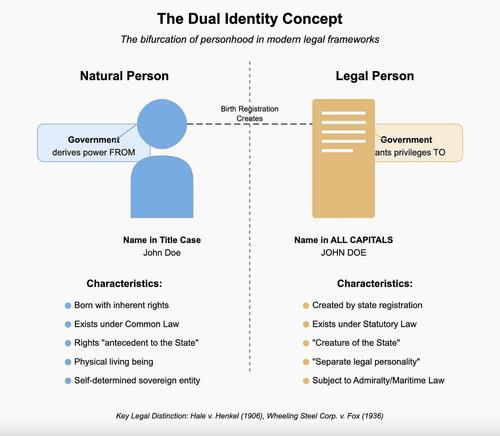

The Dual Identity Paradox: Person vs. Property

Perhaps the most profound aspect of this potential transformation lies in how it redefines individual identity itself. Legal experts examining Treasury regulations and birth certificate processes have identified a curious phenomenon: the creation of what appears to be a dual identity for every citizen.

“While you are technically a person, you’ve entered into contracts that you’re completely unaware of, such as your birth certificate, social security number, et cetera,” notes legal researcher Irwin Schiff. The distinction between natural persons and corporate entities, firmly established in cases like Hale v. Henkel and Wheeling Steel Corp. v. Fox, creates a legal framework in which different rules apply to each. Some legal analysts have questioned whether standardized identification systems effectively create a separate ‘legal person’ distinct from the natural person – a concept sometimes referred to in legal theory as a ‘legal fiction’ – through which government agencies primarily interact with citizens. While this interpretation remains outside mainstream jurisprudence, the documented legal distinction between natural and juridical persons provides context for examining how administrative systems categorize and process citizen identity.

This legal distinction finds further support in the landmark case Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad (1886), in which the Supreme Court’s headnote famously declared that corporations are “persons” under the Fourteenth Amendment. While the Court itself never explicitly ruled on corporate personhood in its official opinion, this headnote nonetheless became the foundation for over a century of jurisprudence treating corporations as legal persons. Treasury regulations further codify this separation between natural persons and legal entities. Department of Treasury Publication 1075 (Tax Information Security Guidelines) establishes protocols for handling taxpayer identifying information through standardized formatting, including the use of capitalized names on official documents. Meanwhile, UCC §1-201(28) defines “organization” to include “legal representatives” in a way that some legal analysts suggest could encompass the registered legal identity created through birth certification, though mainstream legal interpretation differs on this point.

The formalization of citizen identity through documentation has evolved substantially over the past century. Research demonstrates that birth registration systems serve multiple government functions beyond vital statistics – establishing citizenship status, enabling taxation tracking, and facilitating social welfare program eligibility. The formalization of citizen identity through documentation has evolved substantially over the past century. Research demonstrates that birth registration systems serve multiple government functions beyond vital statistics – establishing citizenship status, enabling taxation tracking, and facilitating social welfare program eligibility. This distinction manifests in how legal systems interact with individuals versus their documented identities. When institutions address your name in all capital letters or with a title (Mr./Mrs.), they are effectively engaging with the legal fiction rather than the natural person. This creates a functional bifurcation where administrative systems primarily interface with the paper entity created through registration, while the flesh-and-blood individual exists in a separate legal framework—a subtle but profound shift that fundamentally alters the relationship between citizens and governance structures

While mainstream legal interpretation views these systems as administrative necessities, some legal theorists like Mary Elizabeth Croft have questioned whether the standardization of naming conventions in official documents (including the use of capitalized names) signifies a more fundamental shift in the legal relationship between individuals and the state. These questions, while speculative, reflect broader concerns about how administrative systems increasingly mediate the relationship between citizens and government.

These questions find contextual support in specific Treasury operations. The U.S. Department of Commerce tracks birth certificates through the Census Bureau’s Statistics of the United States reports. Each birth certificate receives a unique number that flows through the Federal Reserve System’s bookkeeping as outlined in their Modern Money Mechanics publication. This registration creates what Treasury terminology refers to as a “Certificate of Indebtedness” with specific registration procedures under Treasury Direct accounts. While mainstream financial analysts interpret these systems as mere administrative tracking, UCC §9-105 defines a “certified security” in terms that could potentially apply to registered birth certificates, particularly when considered alongside UCC §9-311 which governs perfection of security interests by governmental filing – a system that parallels birth registration processes.

Some researchers, including David Robinson in his book Meet Your Strawman and Whatever You Want to Know, propose a legal theory suggesting that birth certificates create a separate legal entity – sometimes called a ‘strawman’ – distinct from the natural person. While mainstream legal perspectives and court decisions have consistently rejected these interpretations, proponents point to the peculiar use of all-capital letters in government documents and the assignment of numerical identifiers as evidence for this dual-identity framework.

If you’re thinking this sounds far-fetched, I understand. The more moderate interpretation sees these identification systems as primarily developing to meet practical governance needs – standardizing citizenship records, enabling social services, and creating consistent legal identities – rather than as financial instruments. Yet even this pragmatic view acknowledges that these systems fundamentally altered the citizen-state relationship in ways most people don’t fully comprehend. I had the same reaction. But before dismissing it entirely, I’d encourage you to examine your own documentation – the all-caps name on your driver’s license, the statement on your Social Security card declaring it remains property of the government agency that issued it. The frameworks we’re discussing are hiding in plain sight, in documents we interact with daily but rarely question.

It’s important to acknowledge that courts have consistently rejected these interpretations on both procedural and substantive grounds, and constitutional scholars maintain that birth certificates developed primarily for practical purposes – tracking demographics, establishing citizenship, and enabling access to public services – not as financial instruments. While there is indeed a legal distinction between natural persons and corporate entities (as established in Hale v. Henkel), mainstream legal perspective holds that this doesn’t support claims about birth registration creating financial collateral. Nevertheless, the development of these identification systems and the expansion of banking frameworks did take place in parallel and enabled novel administratively-mediated relationships between individuals and the state.

These abstract transformations have concrete impacts on citizens’ daily lives. Consider property taxation: while the Constitutional framework treated property ownership as a fundamental right with strong protections, today’s administrative processes can result in government seizure of a family home for unpaid property taxes – even if entirely owned by the family with no outstanding mortgage – often with minimal judicial review. This astounding reality means a homeowner can lose their full equity over relatively minor tax delinquencies. Over 5 million Americans faced property tax foreclosure proceedings in the past decade, illustrating how administrative efficiency increasingly supersedes rights-based ownership.

These systems taken together make up the foundation for what I’ve previously described as a comprehensive architecture for tracking human activity – from financial transactions to medical histories to physical movement – marking a profound shift in how governance structures interface with human life.

The documented evolution of identity administration – from optional recording of births to mandatory registration with unique identifiers – represents a fundamental reshaping of the individual’s relationship to the state. As we’ll explore next, these systems created the administrative infrastructure necessary for implementing large-scale governance changes through legal frameworks that few citizens would ever directly examine.

It is not necessary to accept the more speculative aspects of the strawman theory in order to observe and consider how the increasing documentation and registration of citizens coincide with expanding financial systems. The growth of birth registration, Social Security numbering, and taxpayer identification systems did create new ways of categorizing and tracking citizens that closely aligned with significant changes in banking and finance – a documented correlation worth examining regardless of one’s interpretation of its meaning.

This legal fiction concept has deeper historical roots than many realize. The Cestui Que Vie Act of 1666, passed by the English Parliament following the Great London Fire, established a framework for treating someone as legally “dead” while physically alive. When a person was considered “lost beyond the seas” or otherwise missing for seven years, they could be legally presumed dead – creating one of the first systematic distinctions between physical existence and legal status.

Legal historian David Seipp notes that this created a framework where “the cestui que vie” (the beneficiary of a trust) could be legally distinct from their physical person. While originally addressing property rights during periods of significant displacement, this concept of legally-constructed identity separate from the natural person established a precedent that would later influence modern legal frameworks. British parliamentary records confirm that this Act remains active law under reference ‘aep/Cha2/18-19/11’, with amendments recorded as recently as 2009 through The Perpetuities and Accumulations Act.

This historical development represents an early example of the legal system’s capacity to create distinct “personhood” categories that operate independently from natural existence – a concept that would evolve significantly in later centuries through corporate law and administrative governance structures.

Natural Persons vs. Corporate Entities

This legal distinction between natural persons and corporate entities found formal expression in American jurisprudence through several landmark cases. In Hale v. Henkel (1906), the Supreme Court explicitly distinguished between individual rights and corporate rights, stating: ‘The individual may stand upon his constitutional rights as a citizen… His rights are such as existed by the law of the land long antecedent to the organization of the State… The corporation is a creature of the State.’

This ruling established that legal personhood differs fundamentally from natural personhood. Later, in Wheeling Steel Corp. v. Fox (298 U.S. 193, 1936), the Court further cemented this principle, holding that ‘a corporation can have a separate legal personality from its stockholders.’

This fundamental distinction between natural rights and corporate privileges created by the state remains central to questions about the increasingly corporate nature of governance. The Supreme Court affirmed that corporations exist only by permission of the state, while natural persons exist with inherent rights ‘antecedent to the organization of the State’ – a philosophical distinction with profound implications for understanding modern governance structures.

A Certificate of Incorporation dated July 11, 1919, appears to show an entity named ‘Internal Revenue Tax and Audit Service, Inc.’ chartered in Delaware.” The stated purpose included providing accounting and auditing services ‘in conformity with the Internal Revenue Laws of the United States.’ While conventional historians interpret such entities as service providers contracting with government rather than being the government itself, this this pattern of corporate entities paralleling government functions merits detailed scrutiny in understanding the public-private hybrid nature of American administrative structures.

These legal distinctions introduce a theoretical question about identity itself. If, as some legal researchers suggest, the United States underwent a significant legal transformation in 1871 and banking legislation later modified citizen-government relationships, there could be implications for how we understand liability in the system. According to this perspective, the relationship between citizens and government could be re-conceptualized in terms of asset liability. As constitutional attorney Edwin Vieira Jr. suggests in his analysis of monetary powers, if citizens are treated as assets of the government (rather than the government being the servant of the citizens), this would fundamentally invert the constitutional relationship and potentially shift financial obligations accordingly.

At the core of this analysis emerges a fundamental question: If legal personhood can be separated from natural personhood, does this mean modern citizens exist in a bifurcated legal state – where their physical selves exist under natural law, but their legal identities exist within a corporate-commercial framework? If so, this would align directly with the theory that the United States, post-1871, operates as a managed corporate entity rather than a true constitutional republic. While the 1871 Act explicitly reorganized only Washington DC as a ‘municipal corporation,’ proponents of this theory suggest this had broader implications for the entire nation. They argue that since DC serves as the seat of federal government, establishing it as a corporation effectively created a corporate headquarters from which the rest of the country could be administered under similar principles. This interpretation views the DC reorganization as the first step in a process that would gradually extend corporate governance frameworks throughout the federal structure. Critics maintain this overreaches the Act’s explicit language, which limits its scope to the District itself.

The implications are profound. If these interpretations are correct, then much of what we consider personal financial obligations may rest upon a fundamental misunderstanding of our legal relationship to the governmental corporation itself.

Having examined the potential legal transformation of American governance and citizenship, let’s now consider how similar patterns manifest in contemporary international affairs. In National Suicide: Military Aid to the Soviet Union, Sutton demonstrated that the financial-legal matrix extends globally. He found that approximately 90% of Soviet technological development came from Western transfers and financing – showing how the systems of financial control transcend apparent geopolitical divisions. When rival superpowers are fundamentally supported by the same financial interests, traditional notions of national sovereignty become increasingly questionable. This is but one example of unelected, unaccountable supranational financial interests operating beyond national boundaries and democratic oversight.

The theoretical framework of ‘managed sovereignty’ offers a compelling lens through which to analyze modern geopolitical relationships, particularly in nations experiencing significant external financial influence.

Modern Sovereignty Case Studies

Fiat Nations: Modern Sovereignty as Manufactured Reality

America’s founding governance model operated under clear principles documented in the Declaration of Independence and Constitution. The historical record shows that the Founders explicitly established a system where power flowed upward from the people rather than downward from a sovereign. Over time, however, the relentless addition and overlay of administrative structures onto our Constitutional Republic has resulted in a gradual inversion of this power relationship . As James Wilson, a signer of both the Declaration and Constitution, stated in contemporary accounts: “The supreme power resides in the people, and they never part with it.”

This concept of manufactured sovereignty follows the same pattern across our monetary, scientific, and social systems – all increasingly maintained through decree and collective belief rather than intrinsic substance. Just as our currency derives value from declaration rather than inherent worth, modern governance systems derive legitimacy from administrative authority rather than genuine consent.

This original conception stands in stark contrast to the governance structure that emerged after 1871. If we examine archival evidence from diplomatic communications, banking records, and legal decisions from that period forward, we see sovereignty increasingly treated as a negotiable commodity rather than an inherent right of peoples.

Ukraine: A Current Case Study in Managed Sovereignty

The evolution of external financial pressure creating opportunities for sovereignty restructuring isn’t just historical – it continues to shape geopolitics today. Perhaps no modern example better illustrates this transformation than Ukraine. The documented history reveals a nation whose sovereignty has been repeatedly redefined by external powers.

This pattern began years earlier. In 2008, President George Bush publicly declared strong US support for Ukraine’s NATO membership, stating that “supporting Ukraine’s NATO aspirations benefits all alliance members.” This public commitment to Ukraine’s NATO integration came despite very clear US intelligence assessments warning of potential Russian reaction.

A 2008 classified diplomatic cable (WikiLeaks reference: 08MOSCOW265_a) from then-Ambassador Burns explicitly warned that “Ukrainian entry into NATO is the brightest of all redlines for the Russian elite (not just Putin)… I have yet to find anyone who views Ukraine in NATO as anything other than a direct challenge to Russian interests.”

The case that forces outside of Ukraine were actively managing its sovereignty became even clearer in 2014, when Assistant Secretary of State Victoria Nuland was caught on a leaked phone call discussing the selection of Ukraine’s next leader following the Euromaidan uprising. In this conversation, she told the U.S. Ambassador to Ukraine, Geoffrey Pyatt, “I think Yats [Arseniy Yatsenyuk] is the guy” – demonstrating direct U.S. involvement in picking Ukraine’s post-revolution government.

The Nuland-Pyatt call’s transcript is publicly available, confirming how U.S. intervention shaped Ukraine’s political process at critical junctures.

The financial mechanisms of external control became explicit in Ukraine’s relationship with the IMF following 2014. The IMF’s ‘First Review Under the Extended Arrangement’ for Ukraine, published in August 2015, details extensive “conditionality” requirements affecting domestic policy – including governance reforms, privatization mandates, and financial restructuring. These conditions represent what economic historian Michael Hudson terms “super-sovereignty” – where international financial institutions exercise authority that supersedes elected national governments.

Further reinforcing the managed sovereignty thesis, financial records show that between 2014 and 2022, Ukraine received billions in funding from the IMF and World Bank, with explicit governance conditions attached – creating what economists call “conditionality”, which limited Ukraine’s ability to make independent political decisions.

More recently, in 2023, BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, signed a memorandum of understanding with the Ukrainian government to coordinate investments for reconstruction – further illustrating how financial interests position themselves to influence national development during periods of vulnerability

By following the money and leaked diplomatic cables, we can see a consistent pattern: external control over Ukraine’s political and economic landscape. This pattern reveals how modern sovereignty has increasingly become a fiat construct, manufactured through financial and institutional control.The Ukraine example mirrors the exact pattern we’ve traced in American history – financial vulnerability creating openings for governance restructuring, often implemented by unelected entities with no loyalty to the nation’s constitutional foundations or its people Just as post-Civil War debt potentially facilitated the 1871 Act’s changes, Ukraine’s financial precarity enabled external reshaping of its governance. The parallels are too striking to ignore.

Reflections on Sovereignty

Most people who pay any attention to world affairs understand that puppet states exist. We recognize when foreign governments are propped up, steered by economic leverage, or outright controlled by external forces. The only real debate is over which countries fall into this category.

But why is it that, while many can acknowledge this reality abroad, they reject the mere suggestion that the United States – the most indebted nation in the world, with a financial system tied directly to private banking interests – could be subject to the same forces?

Just as a relatively young nation like Ukraine can be openly shaped by external financial interests, any debt-laden country faces similar vulnerabilities. Why would the world’s most powerful economy, with a staggering $34 trillion in national debt, be immune? The same principles apply, merely at different scales – financial vulnerability creates leverage points for external influence, regardless of a nation’s size or power.

Is it really possible that a nation that borrows endlessly from private financial institutions, whose monetary system is controlled not by its elected representatives but by a private central bank, is somehow completely sovereign?

National Debt and Global Finance

What’s particularly striking in this context is how the national debt might be viewed through principles of public consent and legitimacy. Treasury records show the national debt grew from approximately $2.2 billion in 1871 to over $34 trillion today. Financial records document that this debt is largely held by private banking interest. If citizens are functionally collateral for this debt (as suggested by the unique legal status of birth certificates and Social Security numbers), what does this mean for concepts of freedom and consent?

Even more fundamentally, the paradoxical nature of our monetary system – in which debt is meant to be repaid with debt instruments – represents one of the most significant yet least understood transformations in modern economics.

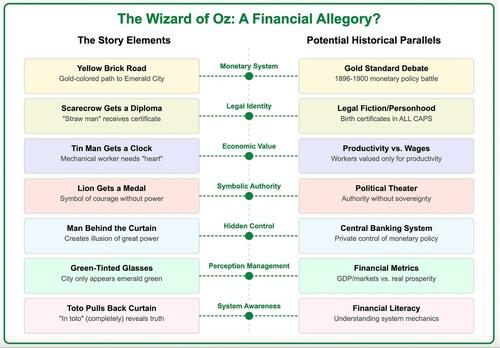

The Wizard of Oz: A Financial Allegory?

Among the most intriguing, though academically contested, interpretations of American culture is the reading of L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz as a potential monetary allegory. Published during the heated debates over the gold standard that dominated the 1896 and 1900 presidential elections, the book contains elements that scholars have identified as potential economic commentary.

The Wizard of Oz struck me differently when I revisited it after this research. What I once enjoyed as a simple fairy tale suddenly revealed itself as something potentially more profound – Dorothy and her companions confront the all-powerful Wizard, only to discover that behind the elaborate illusion is a small, insignificant man manipulating levers. It is a perfect metaphor for how we perceive authority: grand, intimidating, and omnipotent – until we dare to look behind the curtain.

Consider these potential parallels that some scholars have proposed, though it remains debated whether Baum intended these connections:

Dorothy walks the Yellow Brick Road (gold standard) in silver shoes (changed to ruby slippers in the film). This mirrors the major monetary debate of the era – whether to base the dollar solely on gold or to include silver in a bimetallic standard.

The character symbolism extends further into legal and financial frameworks. The Scarecrow – the “straw man” without a brain – offers a particularly compelling parallel to the legal concept of personhood. Legal analysts note that when the Scarecrow asks the Wizard for a brain, he receives only a certificate – much like how a birth certificate creates a legal “person” distinct from the living human being. As attorney Mary Elizabeth Croft explains in her analysis of legal personhood, “The strawman represents the legal fiction created at birth – an entity with no consciousness or will of its own, yet one that interfaces with the financial-legal system.” This interpretation is strengthened by court decisions like Pembina Consolidated Silver Mining Co. v. Pennsylvania (1888), which established precedent for treating non-human entities as legal “persons” under the 14th Amendment. While many legal experts reject the ‘strawman theory’ as an oversimplification of complex legal structures, the parallels remain thought-provoking. Traditional jurisprudence views the personhood distinctions in corporate law as pragmatic legal fictions designed to facilitate commerce, not to convert human identity into financial instruments. Courts have uniformly rejected arguments relying on the strawman theory, which Wikipedia notes is recognized in law as a “scam” and the IRS considers it a frivolous argument and fines people who claim it on their tax returns. Courts have rejected these interpretations primarily on procedural grounds (finding no statutory basis) and by noting that capitalization conventions in legal documents serve administrative purposes rather than creating separate legal entities, and that Congress never explicitly authorized converting citizen status into financial instruments. However, the distinction between natural and legal persons in our governance system – regardless of original intent – has created a dual framework where interactions with government increasingly occur through this legally-constructed identity rather than as natural individuals.

The Tin Woodman presents one of the most fascinating parallels. Beyond representing industrial workers dehumanized by industrialization, some researchers have noted that “TIN” could be read as an early reference to the concept of identification numbers. More specifically, some interpretations suggest ‘TIN’ directly references Taxpayer Identification Numbers. His rusted, frozen state after working himself to exhaustion mirrors how the tax system extracts labor value until citizens are financially immobilized. His search for a heart reflects the spiritual emptiness of a system that reduces humans to economic units. When the Wizard gives him a ticking clock instead of a real heart, it symbolizes how artificial measurements (like GDP, tax revenue, or credit scores) replace genuine human well-being in economic policy.

The Cowardly Lion has been variously interpreted as William Jennings Bryan (the populist presidential candidate) or as representing authority figures who maintain power through intimidation but crumble when challenged. In the story, the Wizard gives him an “Official Recognition Award” – a meaningless credential that nonetheless satisfies his desire for status. Political historians have drawn parallels between the Lion and political figures who have the constitutional authority to challenge financial powers but lack the courage to do so. Congressional records from the debates over the Federal Reserve Act show numerous representatives expressing concern about the legislation while ultimately yielding to banking interests. The medal the Lion receives represents the hollow honors bestowed upon political figures who maintain the status quo rather than confronting entrenched power.

The Wicked Witch of the West with her flying monkey “police” is an interesting parallel to enforcement systems. Historical records show that the period of the book’s publication coincided with the expansion of modern police forces and their increasing use to control labor unrest.

The field of poppies where Dorothy falls asleep presents another curious coincidence. Historical records document that during this exact period, the British Empire had indeed been the world’s largest dealer in opium, particularly in China – a fact established in Parliamentary records and trade documents from the period.

The Emerald City requires visitors to wear green-tinted glasses, creating an illusion of wealth and abundance – perhaps commenting on how the perception of prosperity can be manufactured.

The Wizard himself fabricates an imposing image through elaborate mechanisms while actually being, in his own words, “a very good man, but a very bad Wizard.” The Congressional Record from the period contains numerous speeches comparing the banking establishment to manipulative wizards creating illusions of prosperity while hiding the mechanics of their control.

The role of Toto as truth-revealer gains additional significance when considering the Latin root of his name. “In toto” means “in all” or “completely” – suggesting that only through complete awareness can the illusions of power be dispelled. Just as Toto pulls back the curtain on the Wizard’s elaborate machinery of deception, comprehensive examination of legal and financial structures reveals the mechanisms behind monetary policy and governance. This awareness represents what legal scholar Bernard Lietaer termed “monetary literacy – the ability to see beyond official narratives about financial systems.

Similar to a constructed reality in popular fiction in which an unsuspecting protagonist lives within a controlled environment, the financial and governance systems that shape our daily lives operate behind a carefully maintained façade. Manufactured perceptions – whether of prosperity, security, or freedom – serve as powerful tools for social management, a pattern that repeats across multiple domains of contemporary life.

Whether Baum consciously intended these parallels remains debated by literary scholars, with some maintaining the book was written primarily as children’s entertainment. Regardless, the alignment between the story’s elements and the monetary debates of its time is well-documented in multiple academic analyses. Stories often serve as vehicles for ideas that might be too controversial if presented directly. Could “The Wizard of Oz” be among the most successful examples of encoding economic critique in popular culture?

If this reading of a beloved children’s story seems far-fetched, I understand. I felt the same way initially. But just as I began noticing patterns once I looked for them, I invite you to consider these symbols with fresh eyes. What initially appears coincidental might reveal deeper design when examined collectively.

Examining the Evidence

If we apply the approach Mark Schiffer outlined in ‘The Pattern Recognition Era,’ we should look for consistent patterns across multiple sources rather than relying on single authorities. When we examine the historical record surrounding the 1871 Act and subsequent financial developments, several patterns emerge:

Legal Transformation: The Congressional Record and legal texts from the period show a marked shift in how the United States was described in legal documents before and after 1871. The appearance of “UNITED STATES” in all capital letters (the format typically used for corporations in legal documents) becomes increasingly common after this period.

The documented timeline of these transformations reveals a methodical implementation:

-

1861-1865: The American Civil War creates extraordinary financial pressures that some researchers believe provided the crisis necessary to fundamentally alter the nation’s structure.

-

1862: The Internal Revenue Service is established – initially as a temporary wartime measure.

-

1866: The Civil Rights Act declares all persons born in the US to be citizens, which some legal analysts interpret as converting natural rights into granted privileges within a corporate structure.

-

1871: The District of Columbia Organic Act reorganizes Washington DC’s governance using language consistent with corporate formation.

-

1902: The Pilgrims Society is founded in London and New York, creating an elite transatlantic network connecting financial interests across national boundaries.

-

1913: The 16th Amendment establishes federal income taxation, providing a direct claim on citizens’ productivity.

-

1913: The Federal Reserve Act creates a central banking system—a privately owned entity with remarkable independence from public oversight.

Each of these developments, documented in Congressional records and primary sources, represents a distinct step away from the Constitutional republic established by the Founders toward a system with features more consistent with corporate management than self-governance.

Financial Control: Treasury Department records show that after the 1871 Act, America’s national debt grew substantially and was increasingly held by international banking interests. Primary financial records from this period demonstrate how control over monetary policy gradually shifted from elected officials to private banking interests, culminating in the Federal Reserve Act of 1913.

Global Parallel Development: Diplomatic archives reveal that similar corporate restructuring occurred in other nations during the same period, often following financial crises and always resulting in greater control by international banking interests.

Documentary Discrepancies: When comparing the Constitution to subsequent legal frameworks, particularly the Uniform Commercial Code that now governs most commercial transactions, significant shifts in legal philosophy become apparent. Legal scholars have documented how common law principles were gradually replaced by admiralty and commercial law concepts.

Masonic Connections: The historical record uncovers another intriguing element in this narrative. The Treaty of Washington (1871) Wikipedia page shows images of both British and American signatories displaying what historians have identified as the Masonic “hidden hand” gesture – a specific pose where one hand is tucked into the coat in a particular manner. Historical accounts confirm that Freemasonry was extremely influential among political elites of this period, with membership records showing a significant percentage of government officials belonged to Masonic lodges. This, to a discerning mind, casts doubt on whether negotiations were solely determined by publicly stated national interests, hinting at influential shared affiliations operating beneath the surface.

As Walter Lippmann noted in a quote I examined in “The Information Factory,” “The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society.” One might reasonably interpret the observable changes in America’s legal and financial structures after 1871 to be in service of the ‘conscious and intelligent manipulation’ that Lippmann describes.

Despite months of research on this topic, crucial questions remain. The timing of the transformations described here suggests coordination, but the documentation stops short of proving intent. The identical obelisks in three financial centers could be coincidental, though the statistical probability seems low. And perhaps most puzzling: if these patterns truly represent a fundamental transformation in governance, why has this interpretation remained so thoroughly outside mainstream discourse?

Addressing Mainstream Interpretations

While examining these historical patterns, I’ve carefully considered conventional explanations:

Financial historians like Charles Kindleberger and economic scholars like Ben Bernanke interpret central banking developments as necessary stabilization reforms that reduce economic volatility, rather than as sovereignty transfers.

Administrative law experts such as Jerry Mashaw contend that bureaucratic expansion represented professionalization of governance rather than constitutional restructuring, pointing to continued democratic oversight through congressional budgeting and judicial review.